3d Modelling Paradata

This

study tests the hypothesis

that there is a correlation between a fresco in the House of the Small Palaestra (Pompeii, 8.2.22-23) and the stage of the Large Theatre at Pompeii. An earlier version of this article was published in Didaskalia: Ancient Theatre Today Volume 6 Issue 2 (Summer 2005).

The fresco in the so-called The House of the Small Palaestra depicts a number

of nude human figures who appear to be celebrating victories in

athletic contests. However, the structure in which they are displayed

strongly resembles a Roman theatrical stage of the period, and

does not obviously correspond to any other known type of structure.

Plate 1. The House of the Small Palaestra Fresco

Human figures stand behind opened or partially opened doors on a

podium connected by steps to a stage, which is elevated above ground

level by an articulated pulpitum painted to resemble white marble.

Plate 2. Detail of pulpitum

Plate 3. Detail of podium with steps, supporting extensive architectural

structures

The podium provides the base for a busy combination of aedicules,

hemicycles and projections painted in the red-orange-gold spectrum,

defined and punctuated by a small forest of slender columns.

The walls and doors rising from the podium rather surprisingly

reach only to elbow height of the athletes, while above and beyond

them, picked out in shades of blue, lies an elegant and delicately

detailed array of receding architectural vistas.

Theatrical masks commonly appear as a decorative element in Roman

wall paintings, but the unusually large scale of the masks placed

upon half-walls at either extent of this fresco-about twice the

size that any of the depicted human figures could wear-suggest that

they may in addition be designed to amplify the theatrical associations

of the setting.

Plate 4. Detail of fresco showing mask

The hypothesis that part of the structure of the scene depicted

in the fresco seems closely to match parts of the extant physical

remains of the Large Theatre at Pompeii was first put forward by

Von Cube in 1906 (see also Bieber, 1961: 232).

Plate 5. The Large Theatre, Pompeii

This report gives a non-technical overview of the problem and our

responses to it, rather than providing a detailed breakdown of the

extensive, complex calculations involved. Its purpose is to establish

that

modern 3D visualisation techniques have an important part to play

in the assessment of existing, as well as the advancement of new,

research hypotheses in this area.

Summary of the Reconstruction Process

All reconstruction processes require two initial reference items:

(a) a plan or plans upon which to base the reconstruction

(b) a starting point to give a fixed point of reference for scale.

Using these two items, it is possible to extend the two-dimensional

perspectival depiction into three dimensions, and to interpolate

this new three-dimensional structure into the physical space of

the actual theatre.

Plate 6. Drawing of fresco, from von Cube, op cit. plate 4.

Human representations within frescoes cannot be assumed to be to

scale; they vary in size apparently relative to their importance

within the scene. If they are intended to depict statues, the question

of scale is equally impossible to gauge. Therefore an alternative

point of reference to human figures must be found.

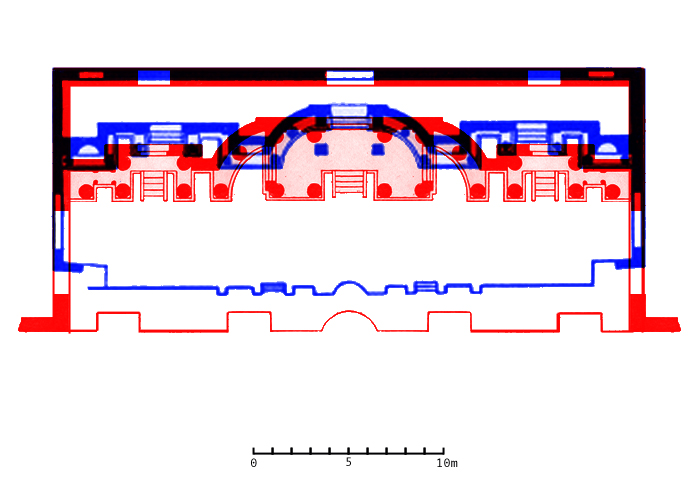

Figure 1, below, shows a plan of the Large Theatre at Pompeii (Maiuri

1951, reproduced in Bieber 1961, fig. 608) overlaid with Von Cube's

hypothetical, schematic plan of the structure depicted in the House of the Small Palaestra fresco (red).

Figure 1. Overlaid plans of the Large Theatre at Pompei (blue),

and the structure depicted in the House of the Small Palaestra fresco (red)

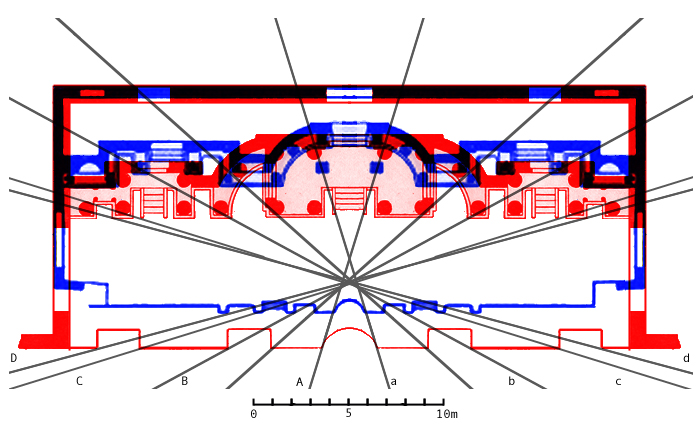

When the pulpitum of the actual theatre is lined up with the pulpitum

depicted in the fresco plan, the relationship between the two structures'

perspectival lines can be traced, as in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2. Perspectival lines correlating the Large Theatre at Pompei

(blue) with the structure depicted in the House of the Small Palaestra fresco

(red)

Unlike the actual theatre, in the fresco the articulated section

of the pulpitum and the frons scaenae are same width. I therefore

propose a viewing position which, in the actual theatre, would achieve

this effect as the perspective implied by the fresco. This gives

a point of reference for depth and scale. Taking this element as

the 0 point on the horizontal axis, it is possible to start calculations.

Working from the "front" of the depiction backwards a

number of observations and comparisons between the fresco and the

theatre can be made.

Using Vitruvian formulae, the height of the fresco's pulpitum should

be approximately 1.147m. Placing the fresco's pulpitum into the

corrected perspective gives it a height of 1.3m, within only 15cms

of the Vitruvian 'ideal'. (The fresco painter's perspectival adjustments,

if uncorrected, would have implied a pulpitum of twice this height:

2.6m.)

The fresco's stage appears to have a platform in the middle of the

curved niche which roughly equates to the two stand-alone podia/column

bases in front of the central opening in the actual theatre's frons scaenae. On the criterion of Vitruvius, these columns (and the others

depicted) appear either to be either non-structural elements, or

to have been aesthetically altered in their proportions for the

sake of the fresco. (There is no evidence in Vitruvius to suggest

that the proportions of wooden architecture normally differed from

those of masonry.)

The purpose of doorways in a frons scaenae is to allow an actor

movement between the fore-stage and rear-stage areas and to conceal

back stage movements. Similarly, non-doorway panels allow actors

to move about the rear of the stage unseen. Adjusted, both doors

and panels in the fresco are sufficiently high to hide the stooped

actor, or to reveal the head and shoulders of an actor if required

- a device often associated with ornamental masks on frescoes of

this nature, and indeed visible on the extremes of this fresco.

Real vs. Fantastical

The next task is to attempt to establish where the rear wall of

the stage would fall if the fresco depiction were to match the real

stage. The rear stage wall in the fresco seems to show a number

of piercings. Except for the central and two flanking doorways,

these are not represented as physical entities on either of the

plans. Contrasting the fresco with other frescoes, it is noted that

the colours are somewhat muted against the vibrancy of the physical

structures, suggesting that this is a receding view or that it is

somewhat "unreal" (e.g. aerial perspective or painted

panels).

The positioning of scenic elements appears to become more perspectivally

warped the further vertically or horizontally removed they are from

the centre of the structure, as if the image were painted on a convex

surface, bulging towards the viewer in the centre. The columns themselves

do not lean, but the decorations behind them do, indicating that

the columns have been very deliberately "corrected" by

the Roman artists to produce a perspectivally coherent framework

through which a perspectivally distorted world can be glimpsed.

The effect becomes more pronounced the further into the scene one

looks.

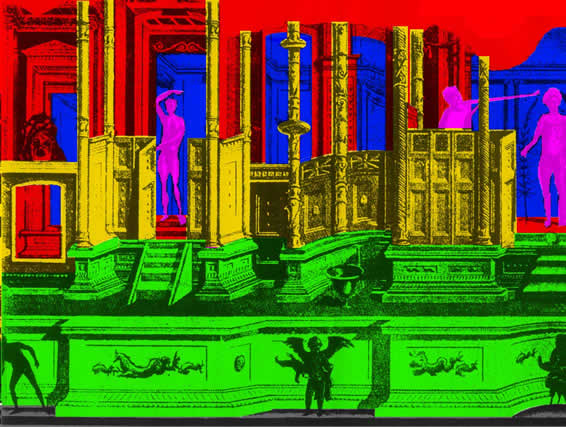

The viewer of the fresco is therefore presented with varying degrees

of reality that recede into the depiction and away from the viewer.

If we were to map these "zones" of reality onto the fresco

by colour coding, they could be presented as follows:

Figure 3. Identified "zones of reality"

Green Zone: This area of the fresco has very close correlation to

both the physical remains of the Large Theatre and to Vitruvius'

formulae for theatre construction.

Yellow Zone: This area appears to be exaggerated in the vertical

axis if the elements are to follow Vitruvian ideals and human scaling.

Red Zone: While the elements in each of the red sections (demarcated

by the yellow columns) are in proportion to each other, all of the

red sections together do not constitute a proportionally or structurally

unified area.

Blue Zone: These areas show elements, or panel-paintings of depicting

elements, that extend beyond the rear wall of the stage building.

Purple Zone: Human depictions.

This manipulation of scale, which will have been more immediately

apparent to a Roman viewer familiar with the scale of the real-world

correlatives of the painted elements, signals the painting's refusal

to be bound by the laws of mimetic representation. Rather than paint

what the eye sees, the artist displays what the mind's eye imagines,

foregrounding what is most important, not necessarily what is most

visible. It is worth noting in this regard that the human figures

are the only elements which are not integrated in perspective or

scale with any other zone within the composition.

The recession of these zones ever further into the fantastical

is analogous to the levels of reality and fantasy encountered upon

actual scaenarum frontes during theatrical performances: behind

the frons scaenae are the most wild, fantastical materials out of

which myths come bodied forth into the reality of the audience.

The Red Zone is made up of a number of compartments distributed

across the width of the painting, separated by Yellow Zone columns.

Each of the two well-preserved Red Zone compartments is perspectivally

consistent within itself, but not with its neighbour, nor with the

perspective of other Zones.

Perspectival inconsistency between compartments allows the painter

incrementally to squash and stretch the non-rectangular subject

matter into the rectangular 'frame' provided by the wall, while

concealing the distortions from the viewer, thereby giving the impression

of a 'realistic' structure, by ensuring that each local section

is perspectivally consistent. In each case, the perspective leads

the viewer deeper into the composition, before the view is blocked

by architectural elements in the next Zone.

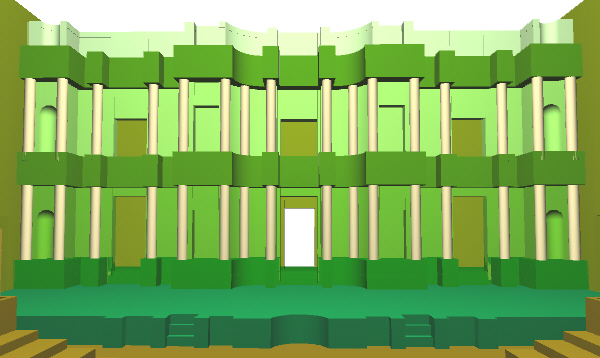

Comparing the Reconstructions

The following images compare our visualisation of the structure

depicted in the fresco at the House of the Small Palaestra with a 3D reconstruction

of the frons scaenae of the Large Theatre at Pompeii based on the

archaeological evidence and the formulae given by Vitruvius in De

Architectura. (Note, the colours used in the frons scaenae visualisation

are purely schematic, enabling the different components of the structure

more clearly to be distinguished than a photo-realistic model would

allow.)

Figure 4. Schematic visualisation of the frons scaenae of the Large

Theatre at Pompeii

If both of the structures are placed side by side, as shown in

Figure 5, it is possible to identify the commonalities between them.